The Downsview framework aims to enhance Toronto's urban landscape by increasing greenspace, housing,

and job opportunities. However, it does not fully address the specific needs of the local community.

Our research analyzes the current conditions at the edges of the framework, where the proposed plan

interacts with the daily lives of existing residents. By assessing these transitional zones, we aim

to identify gaps and opportunities that can inform future urban design strategies.

We highlight the urgent need for affordable, community-based housing clusters that align with the

principles of a 15-minute city, ensuring residents have access to essential services within a short

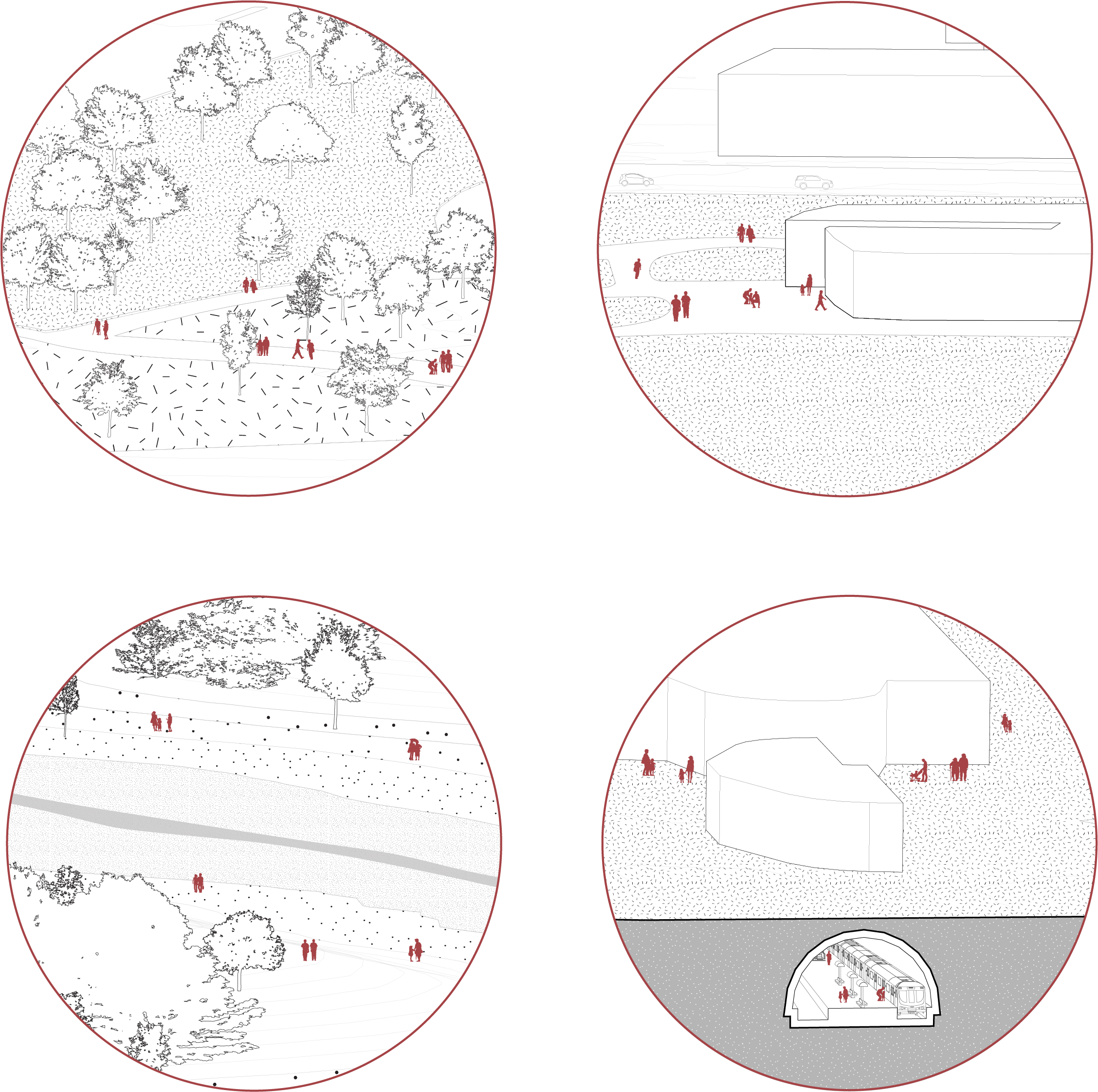

distance. Additionally, we examine how to activate the borders of the site to foster communal

urbanism, enhancing connections to food, recreation, work, and transit. Finally, understanding the

"who" — the distinct groups that make up this vibrant community — is essential for creating an urban

plan that fosters inclusivity and community for all.

“Density should not be understood and measured as an abstract number of objects or

people per area. This mentality produced irresponsible sprawl everywhere, where buildings are

understood as things deposited indiscriminately across a territory without any relation to public

infrastructure…density must be measured instead as the intensity of social and economic exchanges

per area”

-Spatializing Justice Building Blocks by Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman p.68

The area of Downsview belonged to the Territory and Treaty Lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit as well as the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. This area was being settled around 1793 during and after the American Revolution by Loyalists fleeing from the United States.

Named for the view from the elevated lands, Downsview was first settled by John Perkins Bull, who was

given the land by his father in 1830. By 1842, John established a farm and built his house - the

"Downsview House".

After his marriage, John was given the nickname "Squire" by the townspeople as his house was used as

a court and jail. The John Perkins Bull house still stands today at 450 Rustic Road, where it has

found a new purpose as a nursing home.

For over 100 years, Downsview served as an agricultural community with its own general store,

school, and post office.

Photograph of the John Perkins Bull house. 1955. Photo courtesy of Toronto Public Library Archives.

In 1824, three brothers from the Boake family sailed to Canada from Ireland and settled in York Township (Toronto) where their sister, Elzabeth Bull, was already settled. In 1830, the Boakes purchased a large parcel of land that is known today as Downsview Park. Four generations of the Boake family made this area their home until it was expropriated by the military in 1951.

In 1929, William De Havilland purchased 70 acres of farmland along Sheppard Ave to build the De Havilland Aircraft of Canada factory. At the time, it was Canada's largest supplier of aircraft in the 1930s. An optimal site due to its topography, several record-breaking flights were made with aircraft assembled here at the De Havilland factory in Downsview.

De Havilland company employees. 1930s. Photo courtesy of De Havilland Aircraft of Canada.

De Havilland purchased more land and added another hangar and a building, which is now known as the Downsview Park Sports Complex. With the start of WWII, more runways and facilities were built.

In 1946, the airport housed the 400 Squadron RCAF and later the 411 Squadron RCAF. Throughout the Cold War, these two squadrons were responsible for Toronto's air defense.

As of 2016, the immediate area around the park and airport houses over 15,000 people. The neighborhood houses mostly older people, and from 2001 to 2011, the 0-14 year old population shrunk by 6.7%.

The Mississaugas of the Credit, part of the Ojibway nation, control most of what is now Southern Ontario.

The British Crown acquires Downsview Lands from the Mississauga Nation as part of the Toronto Purchase.

SourceJohn Perkins Bull, a key early settler, establishes his farm in the Downsview area, which he calls "Downs View" due to its elevation and scenic views.

SourceToronto's earliest railway is built by Ontario Simcoe Huron Union Railroad, facilitating trade between the three lakes.

An aerial view of Toronto looking east from the foot of Parliament Street, around the time of the OS&H sod-turning.

The region remains largely agricultural, with farming as the primary industry. The area retains its rural character until the early 20th century.

De Havilland Aircraft of Canada opens its factory in Downsview, marking the start of aviation activity in the area. The factory plays a pivotal role in manufacturing military aircraft for the Canadian Armed Forces, especially during WWII.

The Royal Canadian Air Force expropriates properties to enlarge airstrips and establish an RCAF station.

Downsview Airport is officially built as a military base during World War II. It becomes a significant hub for aviation testing and production during the war, cementing its importance in Canada’s defense efforts.

.jpg)

Air-to-air photograph of a De Havilland DH.98 Mosquito B Mk IV Series 2 bomber with No. 105 Squadron of the Royal Air Force in flight.

After the war, De Havilland continues to use the airport for civilian and military aircraft production. The surrounding area begins transitioning from its agricultural roots to a growing industrial and suburban zone with the Baby Boom.

Toronto's post-war suburban boom extends to Downsview. Residential subdivisions replace farmland, transforming Downsview from a rural outpost into a bustling suburban area.

Downsview continues to be a prominent location for the Royal Canadian Air Force, with the military using parts of the base for training and operations.

Canada's first spacecraft is launched - the Alouette 1 Satellite equipped with the STEM antenna, both developed by De Havilland engineers and scientists. The same year, the Department of National Defence expropriates land adjacent to the airport, resulting in the diversion of Sheppard Avenue from its original course.

Pope John Paul II holds a historic mass in Downsview Park during World Youth Day, attracting hundreds of thousands of people and marking one of the largest gatherings in Canadian history.

Bombardier purchases De Havilland Aircraft of Canada.

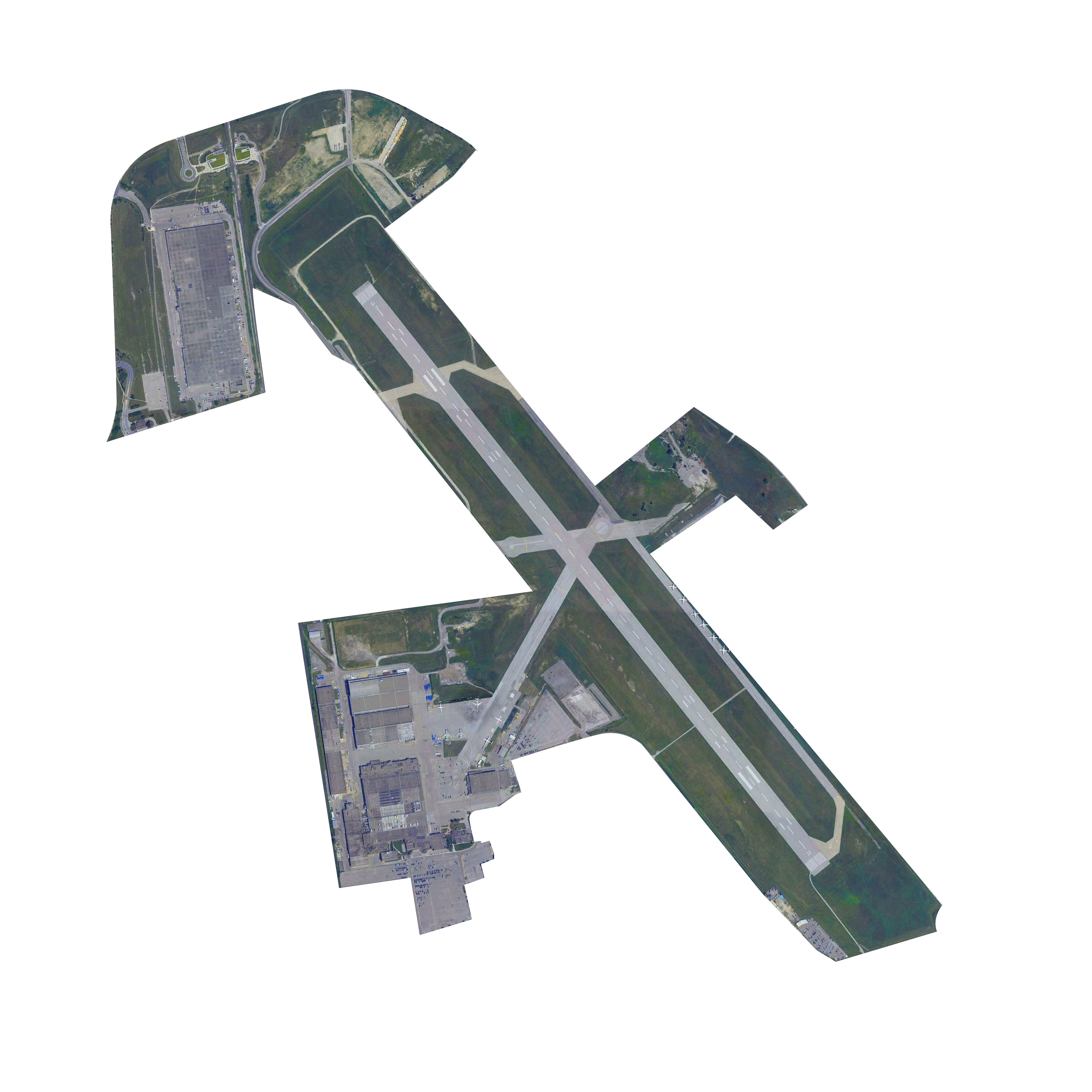

Downsview Airport officially ceases operations as a military base, and much of the land is repurposed into Downsview Park, Canada’s first national urban park.

World youth day takes place at Downsview park.

The opening of Downsview Station (known today as Sheppard West) on the Toronto subway line accelerates urban development, improving access to the area. Downsview becomes more integrated into Toronto’s urban grid, attracting further residential and commercial growth.

Source.OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), led by world-renowned architect Rem Koolhaas, is selected to design the master plan for the Downsview Lands. This visionary proposal imagines Downsview as a vibrant mixed-use community with green spaces, housing, and commercial areas. It emphasizes sustainability, innovation, and urban livability.

Diagram of the OMA masterplan for Downsview. 2000. Image courtesy of OMA.

Molson Canadian Rocks for Toronto is hosted at Downsview Park to help revive Canada's economy after the 2002 SARS outbreaks.

It is recorded as the largest paying rock band concert in the world by Guinness World Records. Source.

Photo of the concert in Downsview Park. 2003. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

A stage collapses at the park before the Radiohead concert, killing one and injuring 3 others.

Downsview stage collapse. 2012. Image courtesy of Toronto Star.

The Downsview Park TTC Subway Station opens, enhancing transit accessibility. It serves as a crucial link for the expanding community and nearby York University.

Bombardier announces the sale of its Downsview site as part of a broader corporate restructuring plan, officially ending its long-standing aviation operations in the area.

Downsview continues to evolve as plans for the Downsview Lands redevelopment move forward. The focus is on creating a balanced, sustainable community that includes housing, commercial spaces, and large green spaces. The redevelopment is expected to house over 100,000 people and offer expansive public parkland.

The area continues to be a site of major urban planning initiatives, including smart city technologies and sustainable living solutions. Downsview’s transformation from a military airport into a modern urban district continues, with future projects emphasizing its importance as a green, innovative community hub.

Over a span of several days, we collected photos, videos, sounds, and stories of the people and places around the site. As we walked around the site, we made notes of our experience and stress levels. This part is best experienced with sound. ♫

Cattails (Typha spp.)

Goldenrod (Solidago spp.)

Common Reed (Phragmites australis)

Thistles (Cirsium spp.)

Frost Aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides)

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

Queen Anne's Lace (Daucus carota)

Chicory (Cichorium intybus)

New England Asters (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae)

They are strongly opposed to the proposed development and believe that funds should be directed towards enhancing existing, inadequate infrastructure such as streets, sidewalks, playgrounds, schools, and community centers. They are concerned about the additional traffic that the development would generate and the increase in noise, which would disrupt the currently peaceful and quiet neighborhood, particularly affecting the elderly residents who value the tranquility of their community.

She is open to welcoming cyclists and pedestrians into the area

but is

opposed to increasing car traffic.

The community is very cohesive, consisting of both young

families and elderly residents.

We interviewed her on the west side of the site while she was

walking

to the park with a friend visiting from Puerto Rico.

She is a resident nurse and member of the community council along

with

her husband.

She described the area as peaceful and safe, noting that there

aren't

many people outside, making it quite quiet.

She mentioned that the East Side is usually much busier and

livelier compared to the West Side.

She also pointed out that there isn't a direct path to travel from the

East to the West; instead, one has to go all the way around

Downsview Airport, which takes 10-15 minutes.

Additionally, she highlighted that the neighborhood has a strong

Italian and Jewish presence.

We interviewed her on the West side.

He mentioned that he doesn’t see anything wrong with the area or the

neighborhood, though he thinks more courts or parks would

always be a nice addition.

He pointed out that they already have direct access to Yorkdale

via

the bus and doesn’t see a need for additional amenities closer to

them, as they all go to Yorkdale.

While he enjoys biking, he noted that there aren’t bike lanes on

the

West Side, only on the East Side.

We interviewed him at a soccer field where he was playing soccer

with

his friends.

She mentioned that she had lived in the area for over 40 years and had seen

it change quite a bit.

She had heard about the new development at the old airport

site.

Part of her was excited because it might bring new shops and

facilities they could use, but she was also worried about increased

traffic and noise.

She hoped they would keep some green spaces and consider long-time

residents in their plans.

He expressed skepticism about the whole thing.

Developments like this tended to raise rent prices, which worried

him.

He hadn't looked into all the details but hoped they would include affordable

housing.

Plus, construction might make his commute tougher than it already

was.

He admitted he didn't know much about it but thought that if they built more stuff

for people his age, like a better skate park or entertainment

spots, that would be cool.

As long as they didn't take away their hangout spots.

We spoke with him at the skate park area within Stanley Greene Park where

he was skateboarding with his friends.

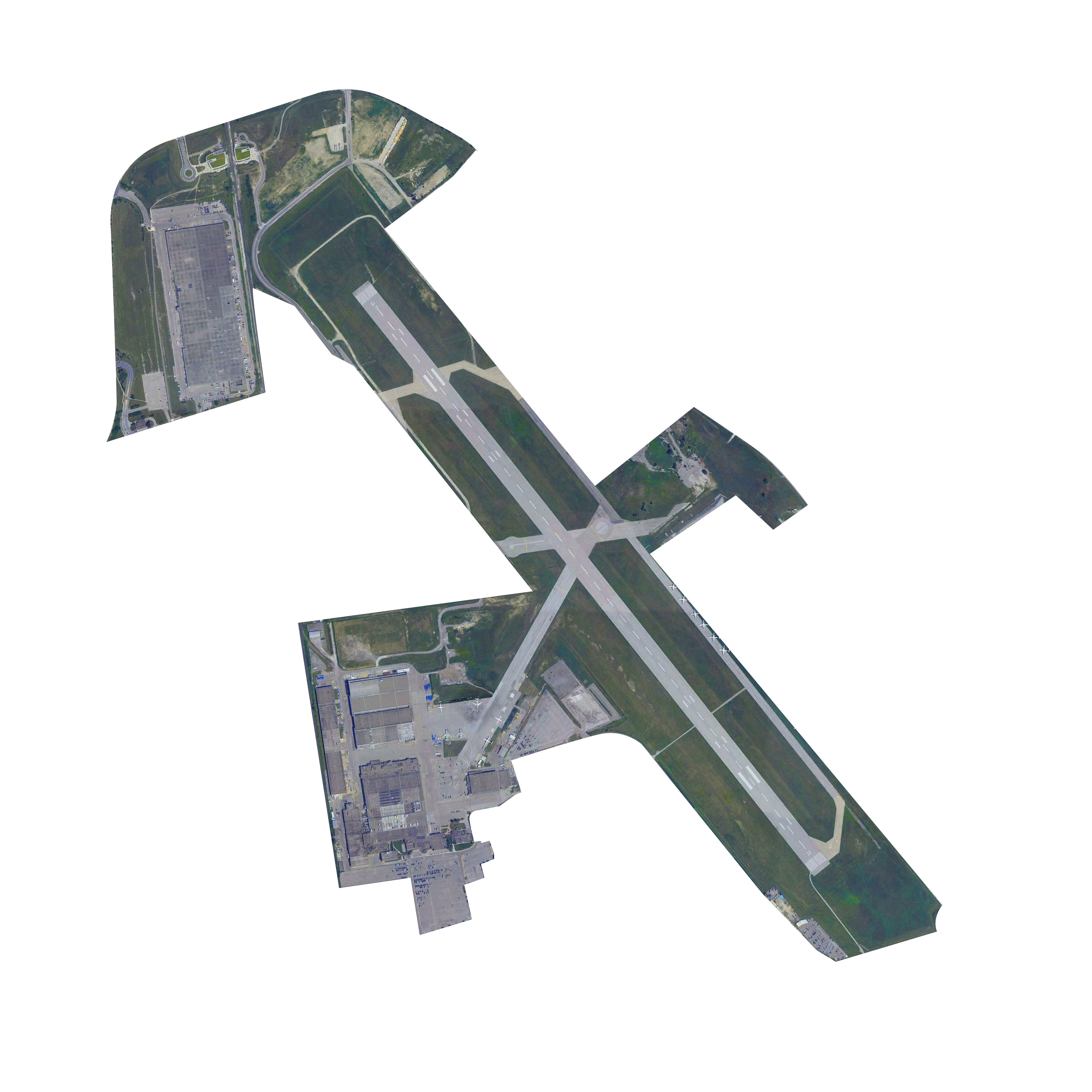

Site (210 hectares)

1.12x High Park (210 hectares / 186 hectares)

High Park (186 hectares)

Site (210 hectares)

19x Queens Park (210 hectares / 11 hectares)

Queens Park (11 hectares)

Site (210 hectares)

170x 1 Spadina Crescent (210 hectares / 1.24 hectares)

1 Spadina Crescent (1.24 hectares)

These map show locations of schools, points of interest, neighbourhood boundaries, and more.

The series of maps contain information about groundcover, hydrology, topography, and pollution.

The series of maps contain information about traffic incidents involving pedestrians, cyclists, and auotmobiles.

Dots represent the distribution of minorities in each cencus dissemination area.

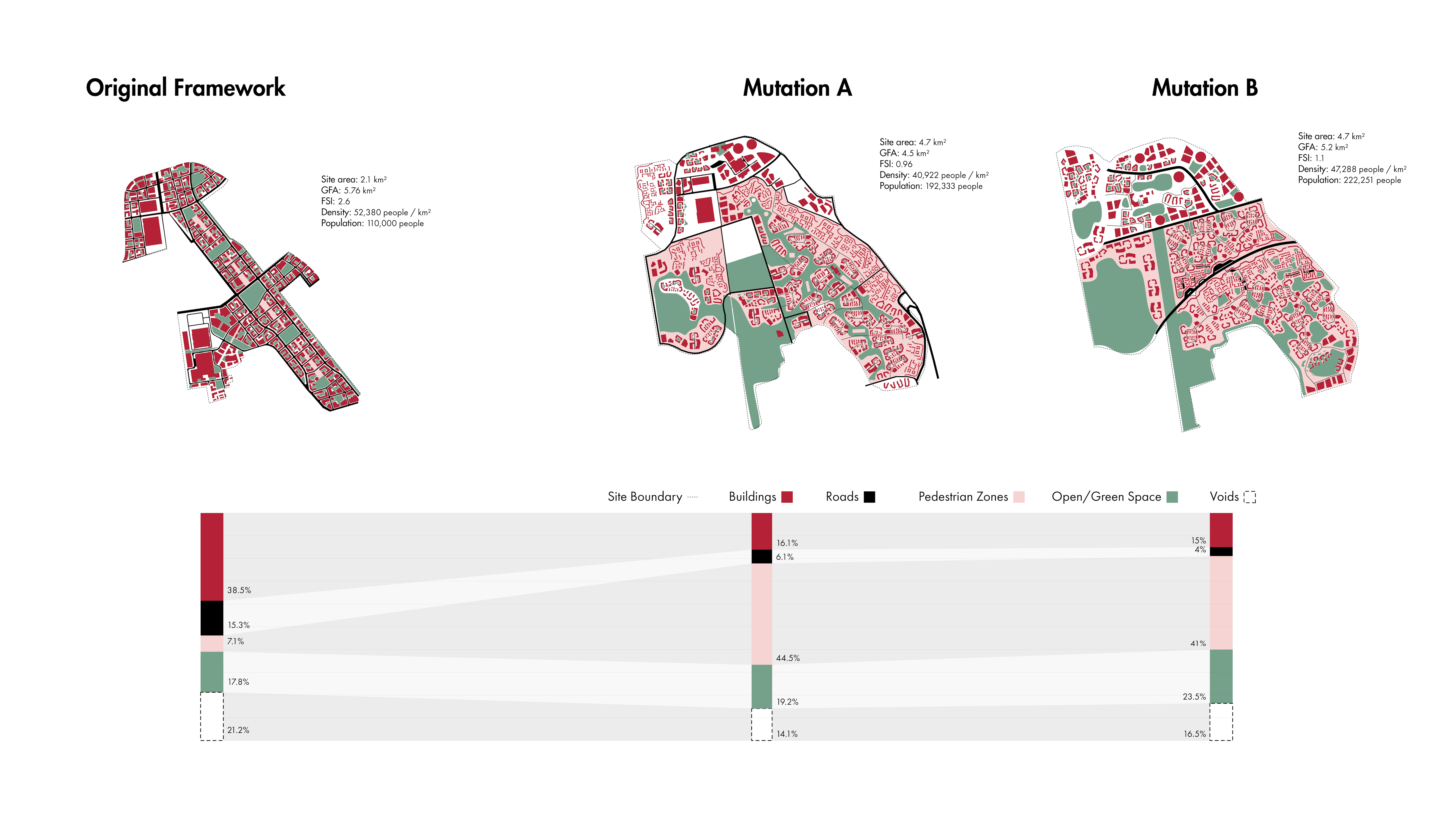

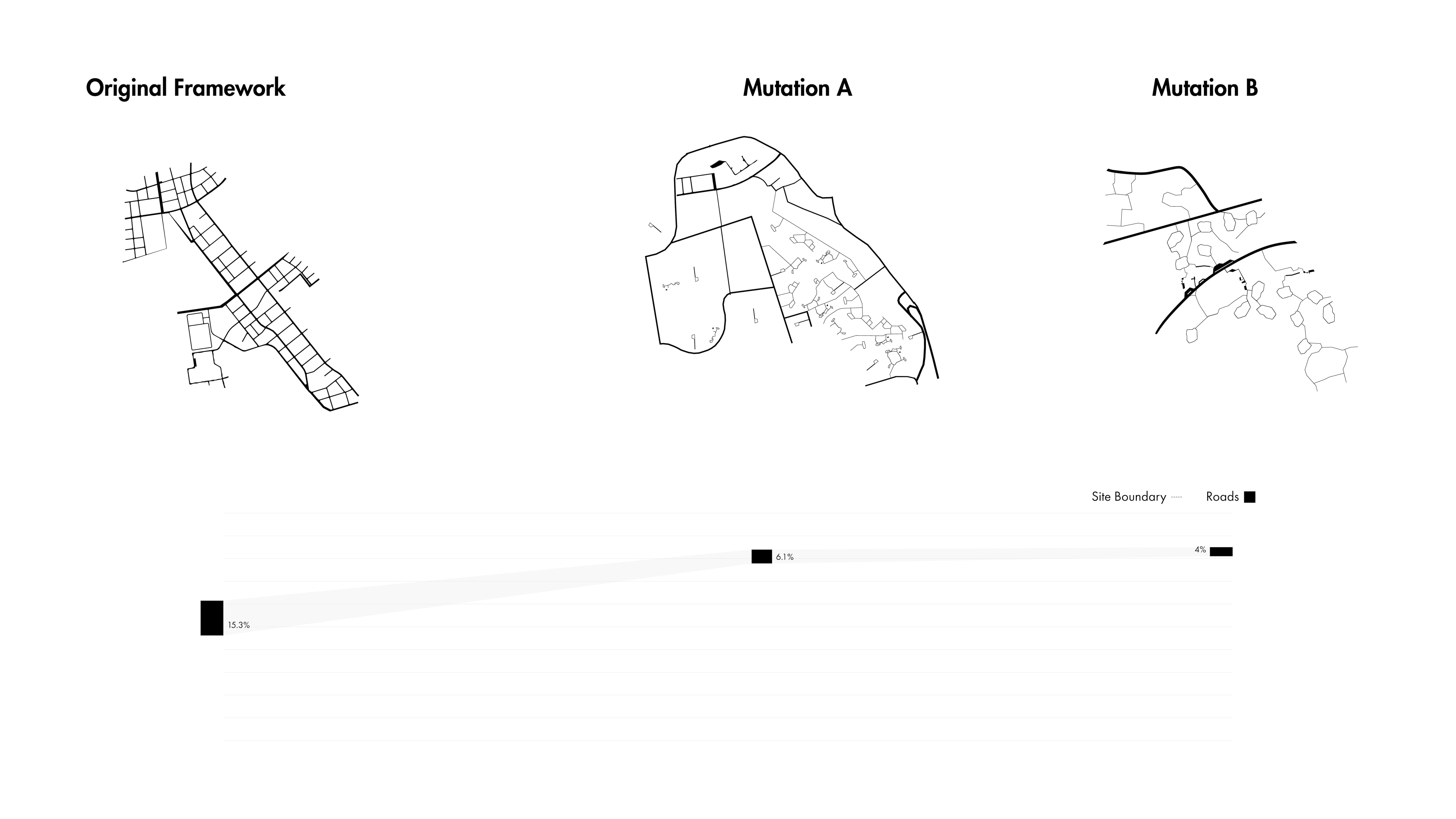

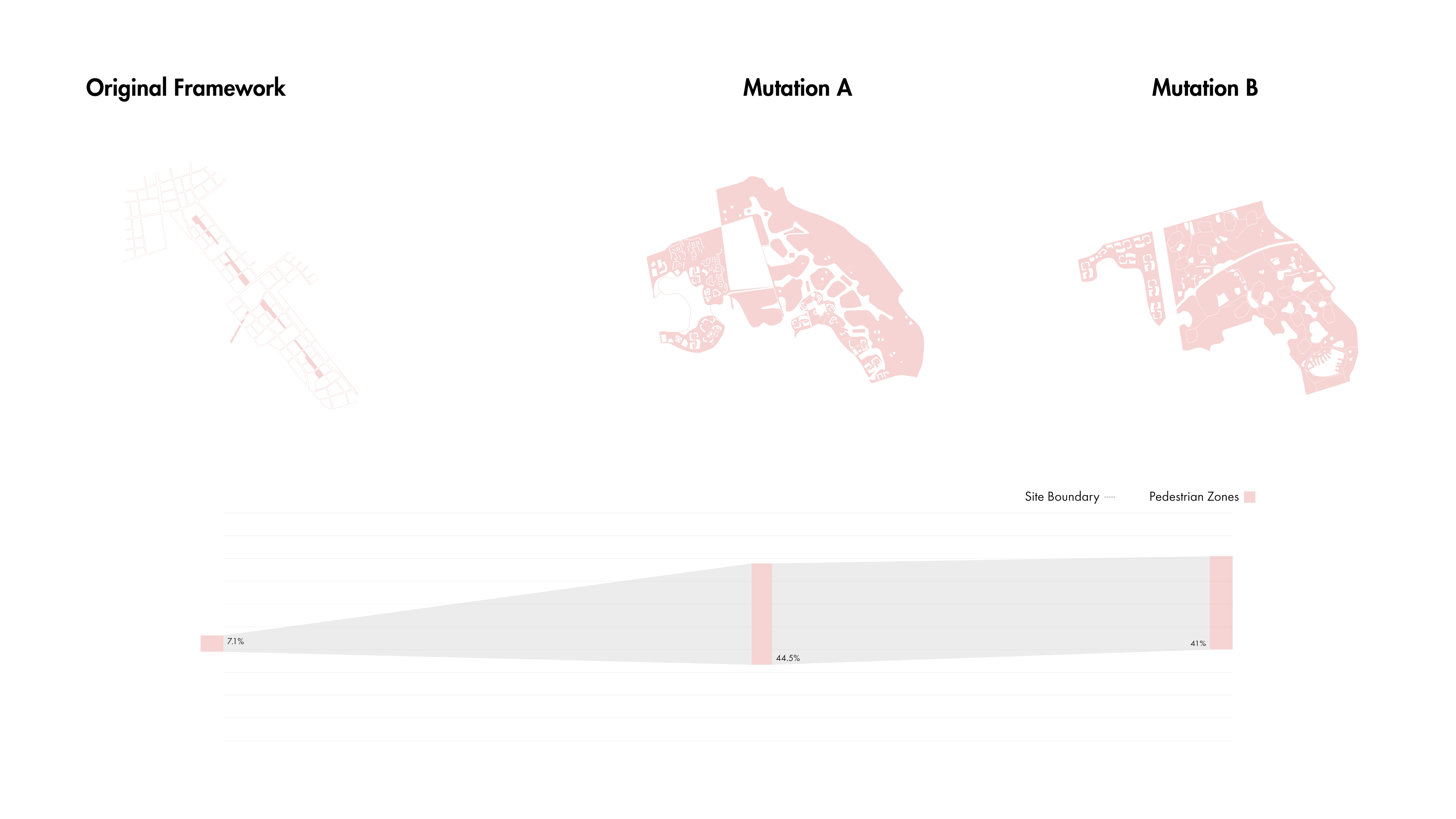

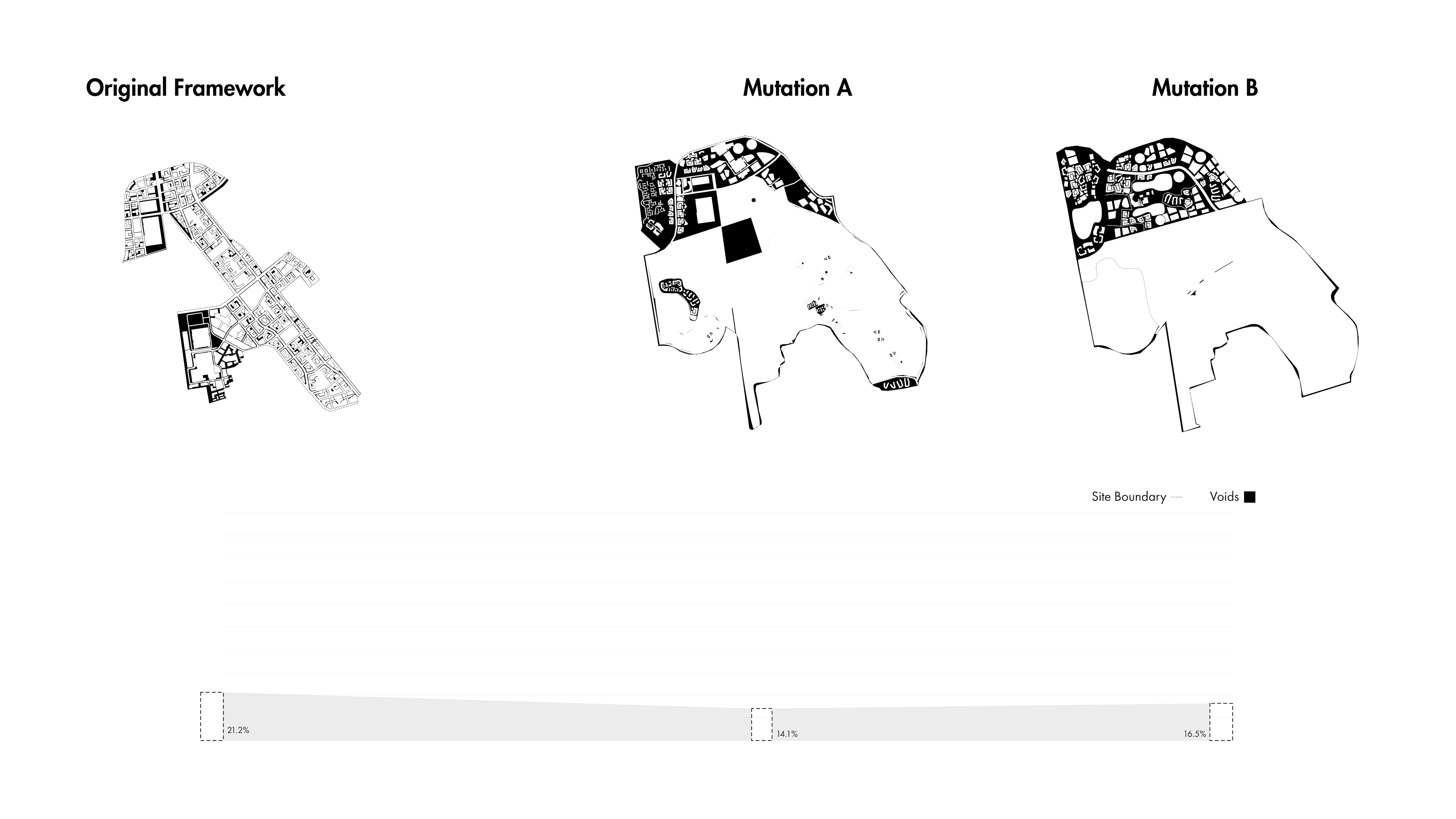

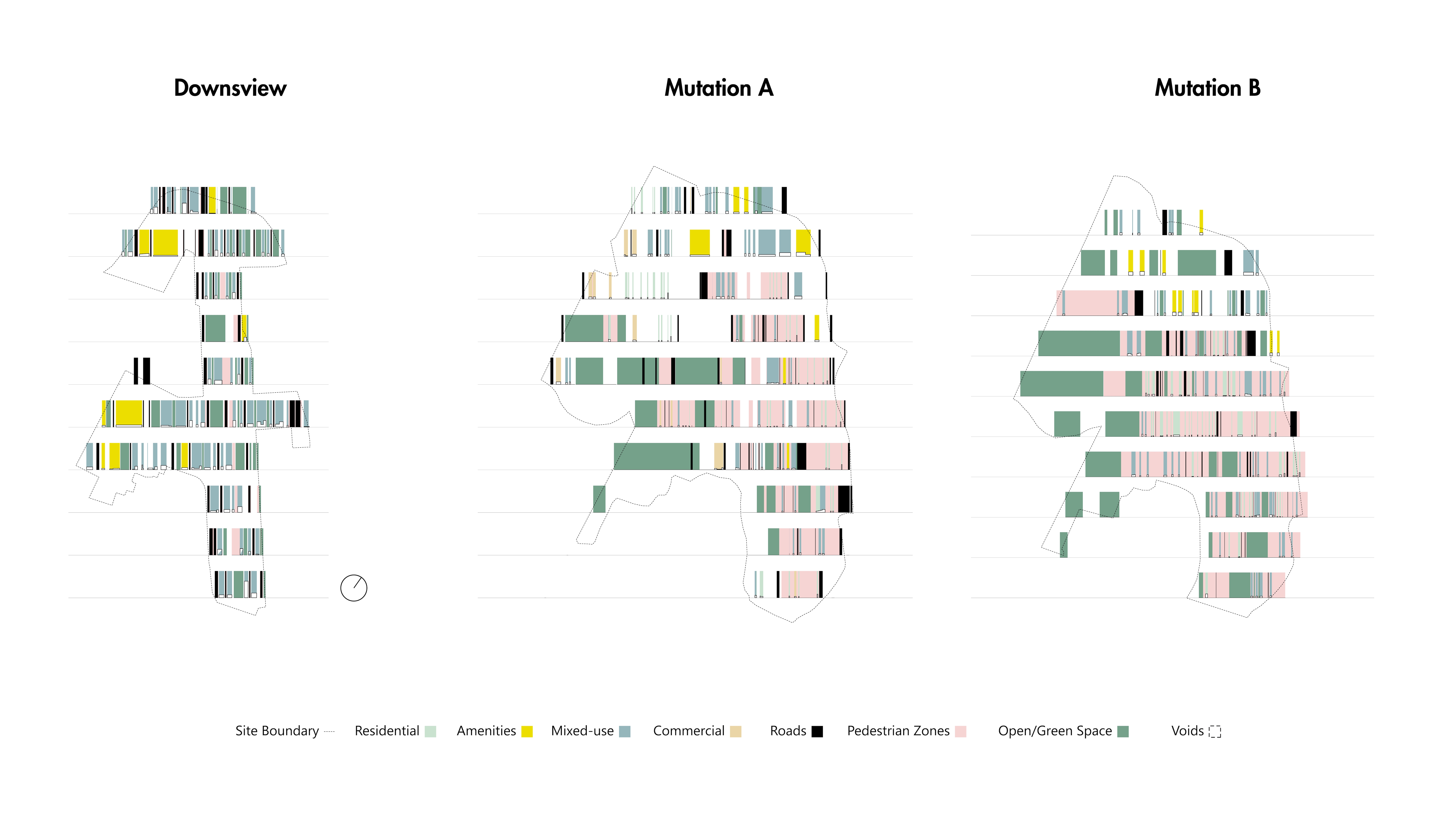

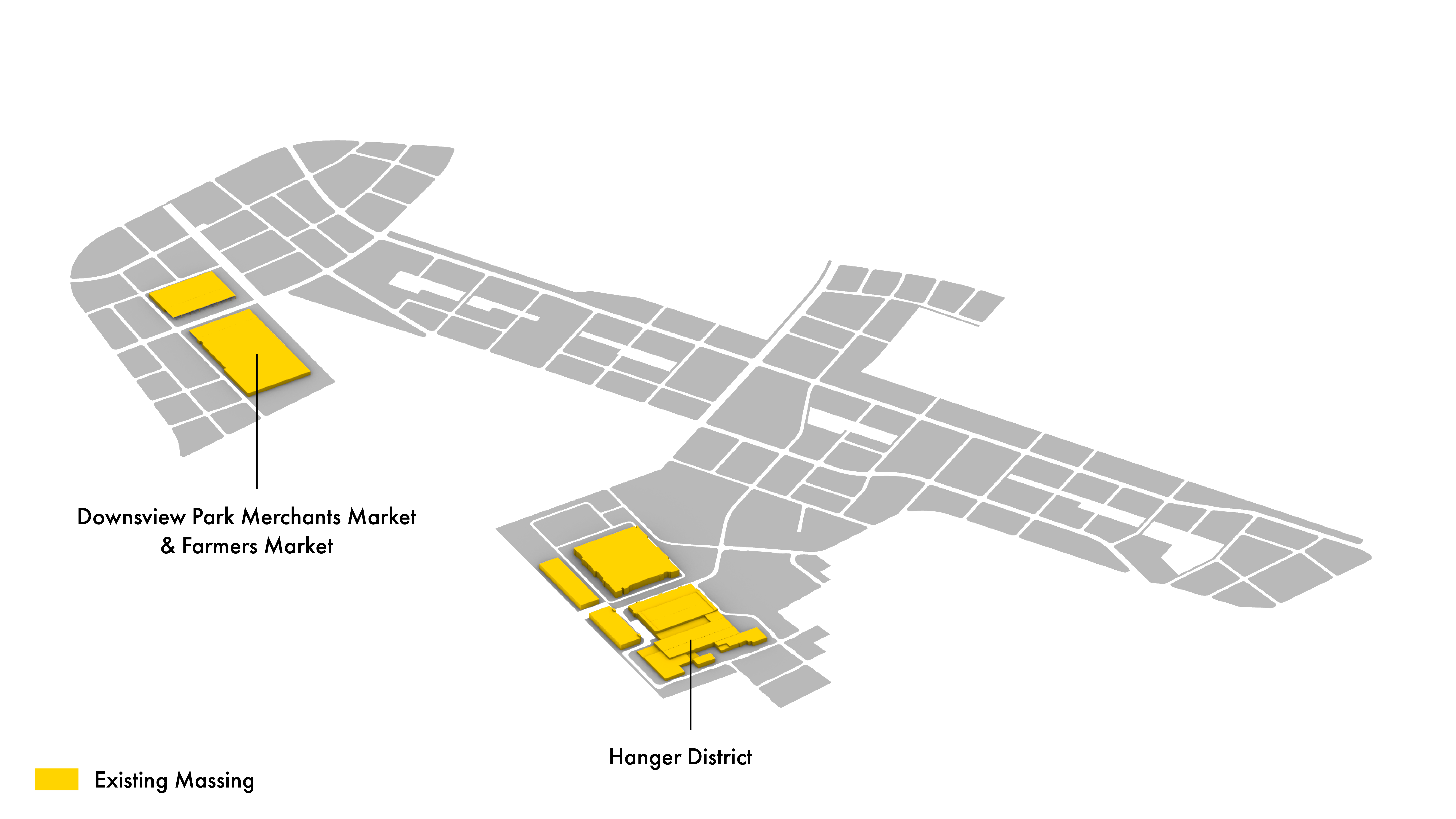

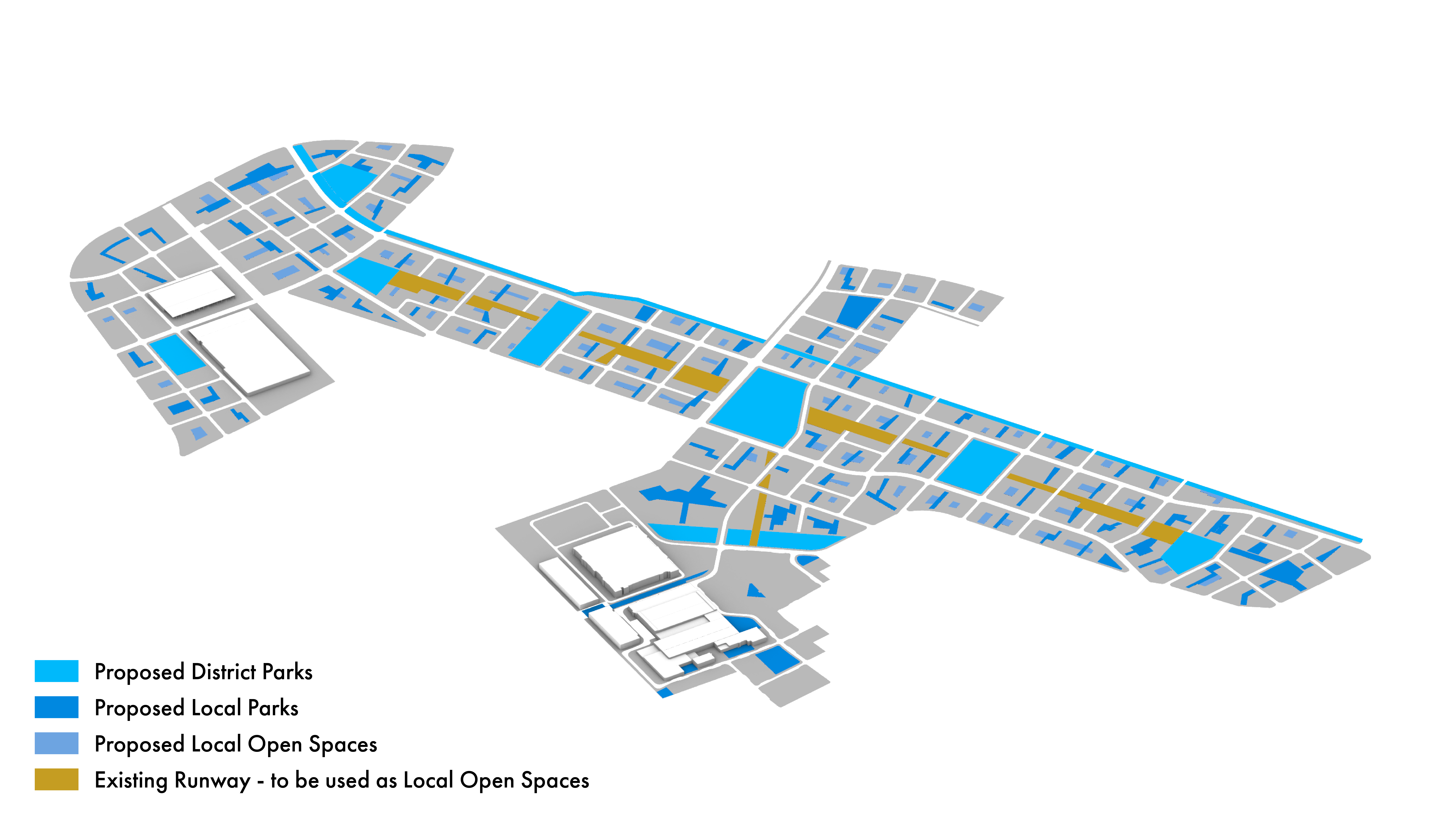

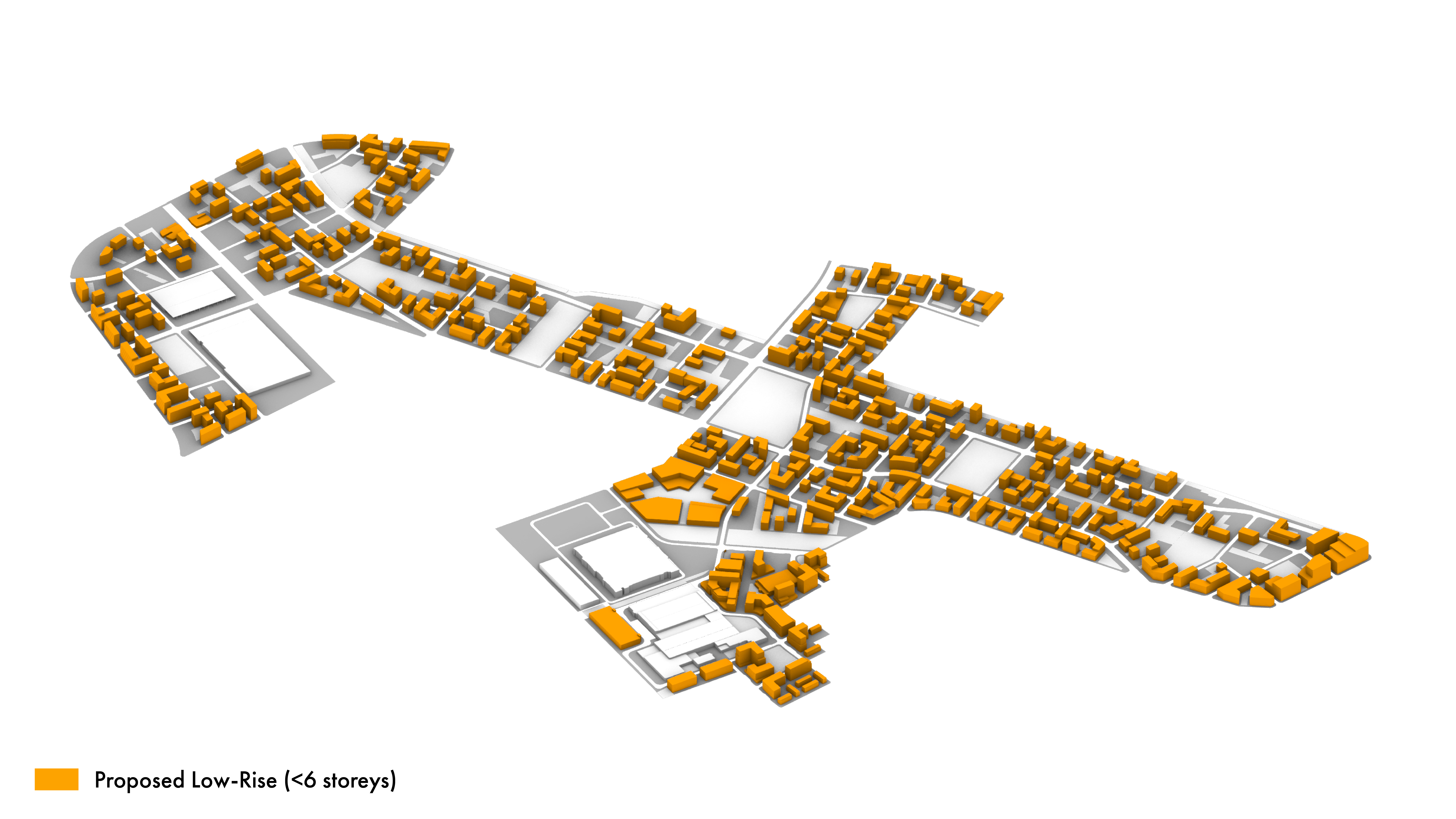

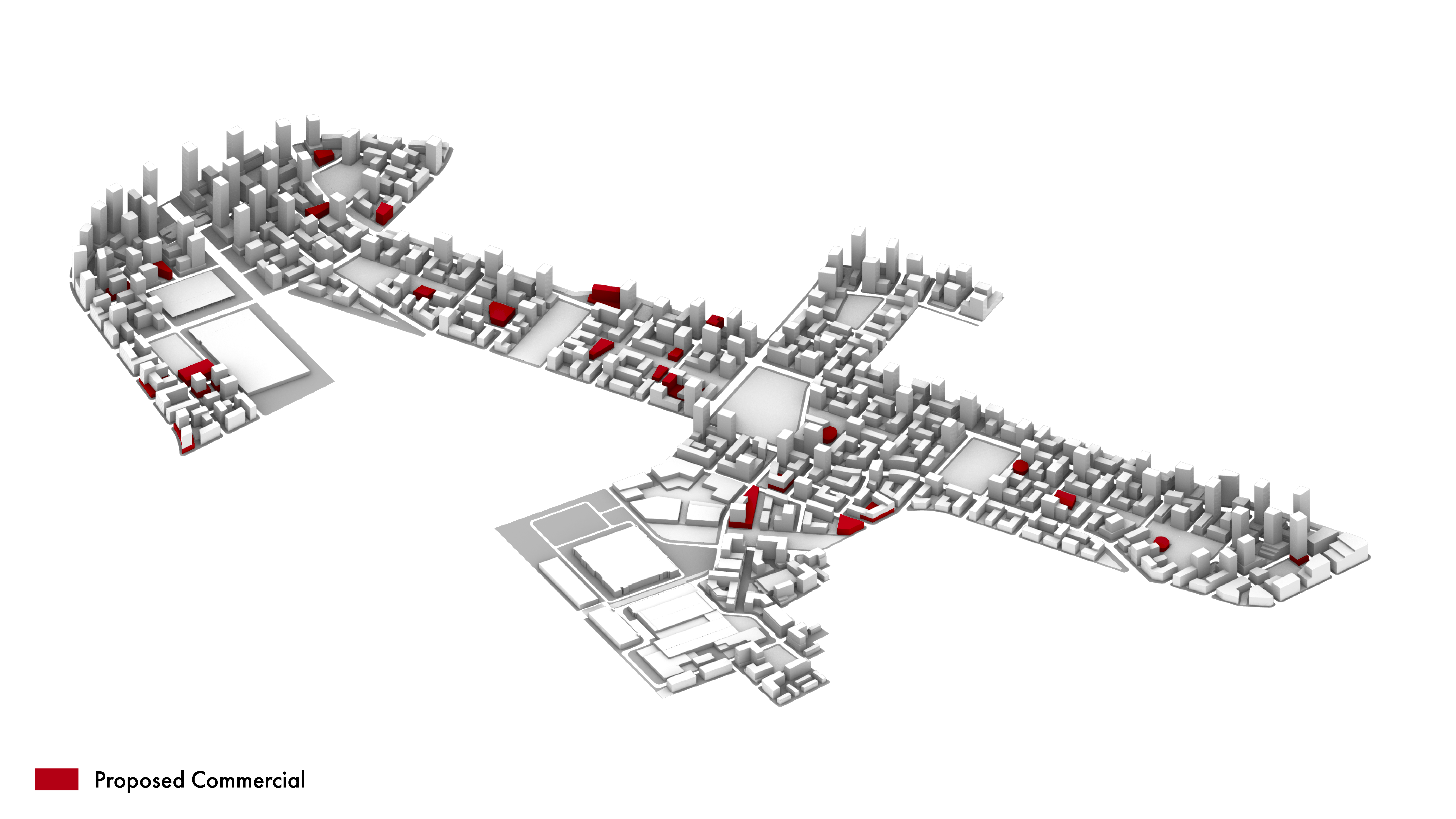

These maps show the proposed building typologies and open spaces.

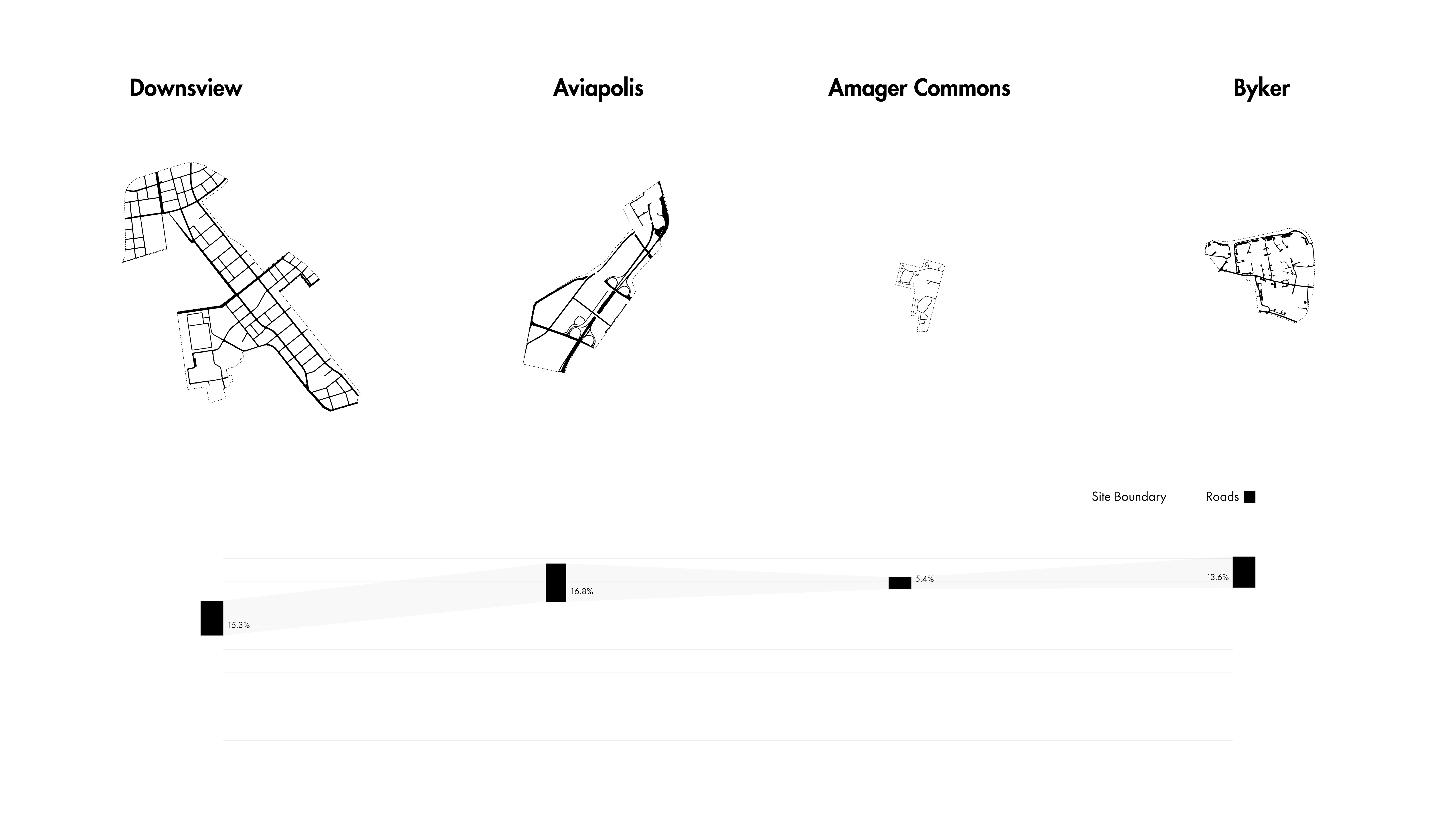

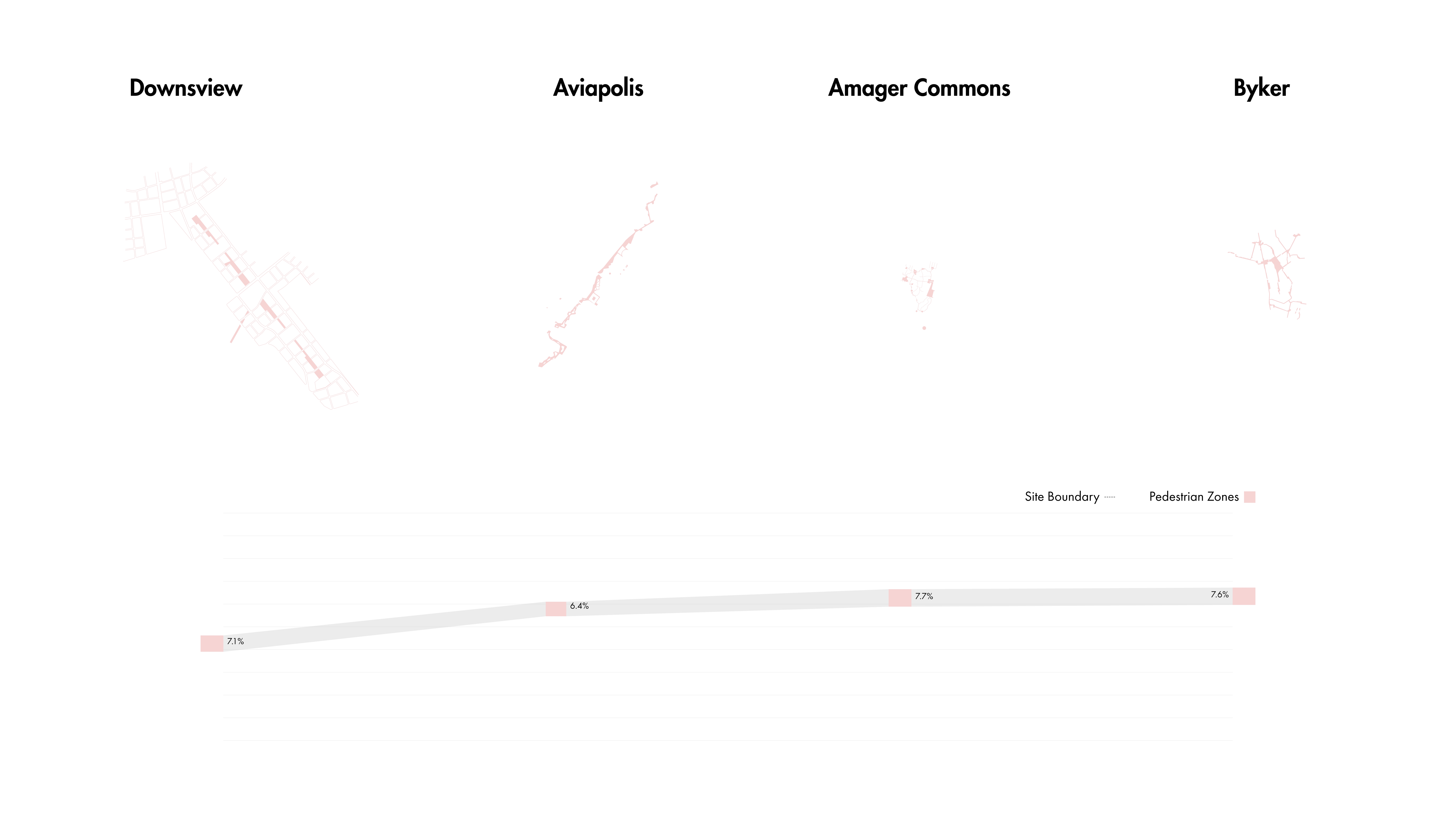

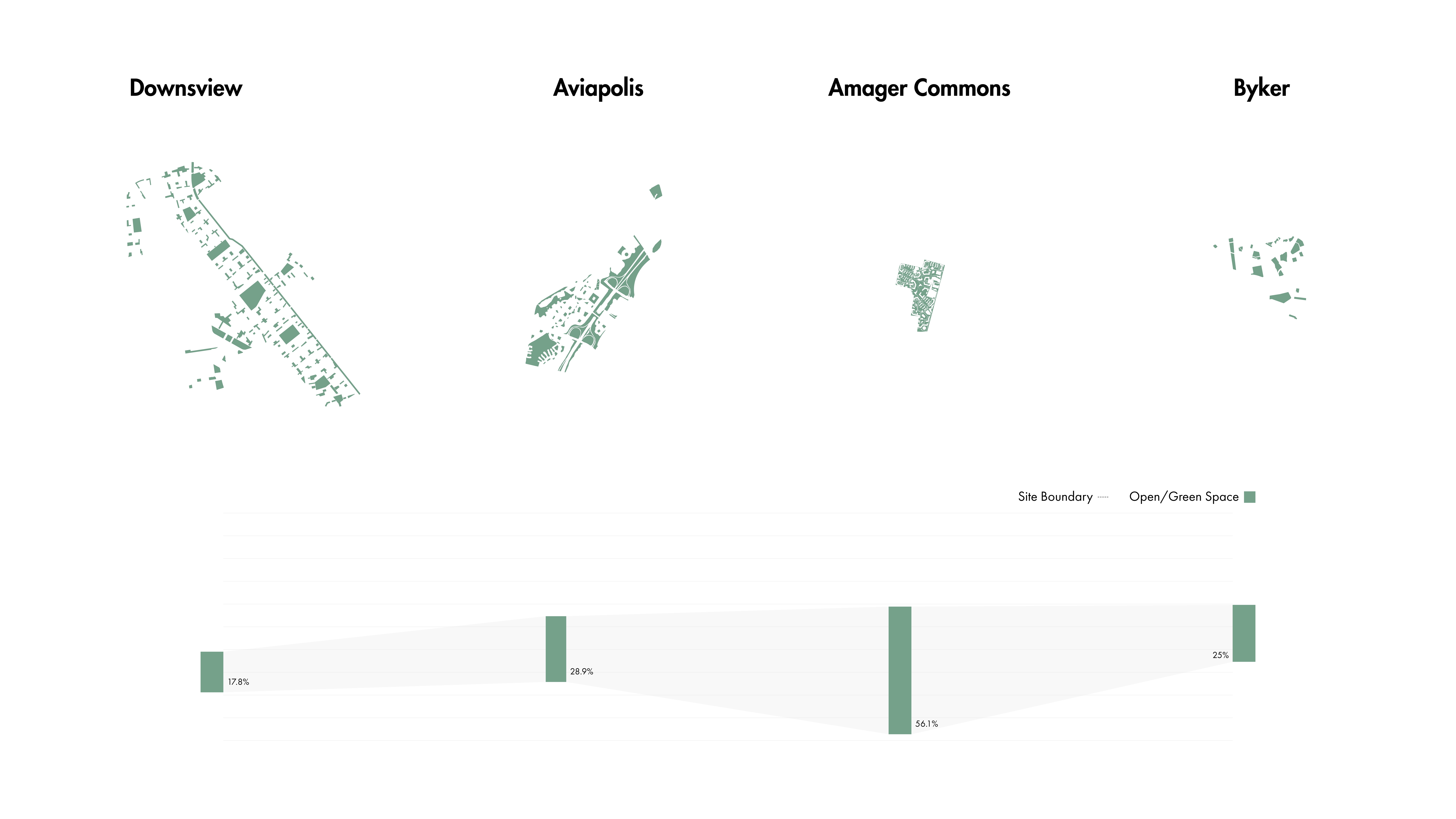

These maps show how people get around the site through various modes of transportation.

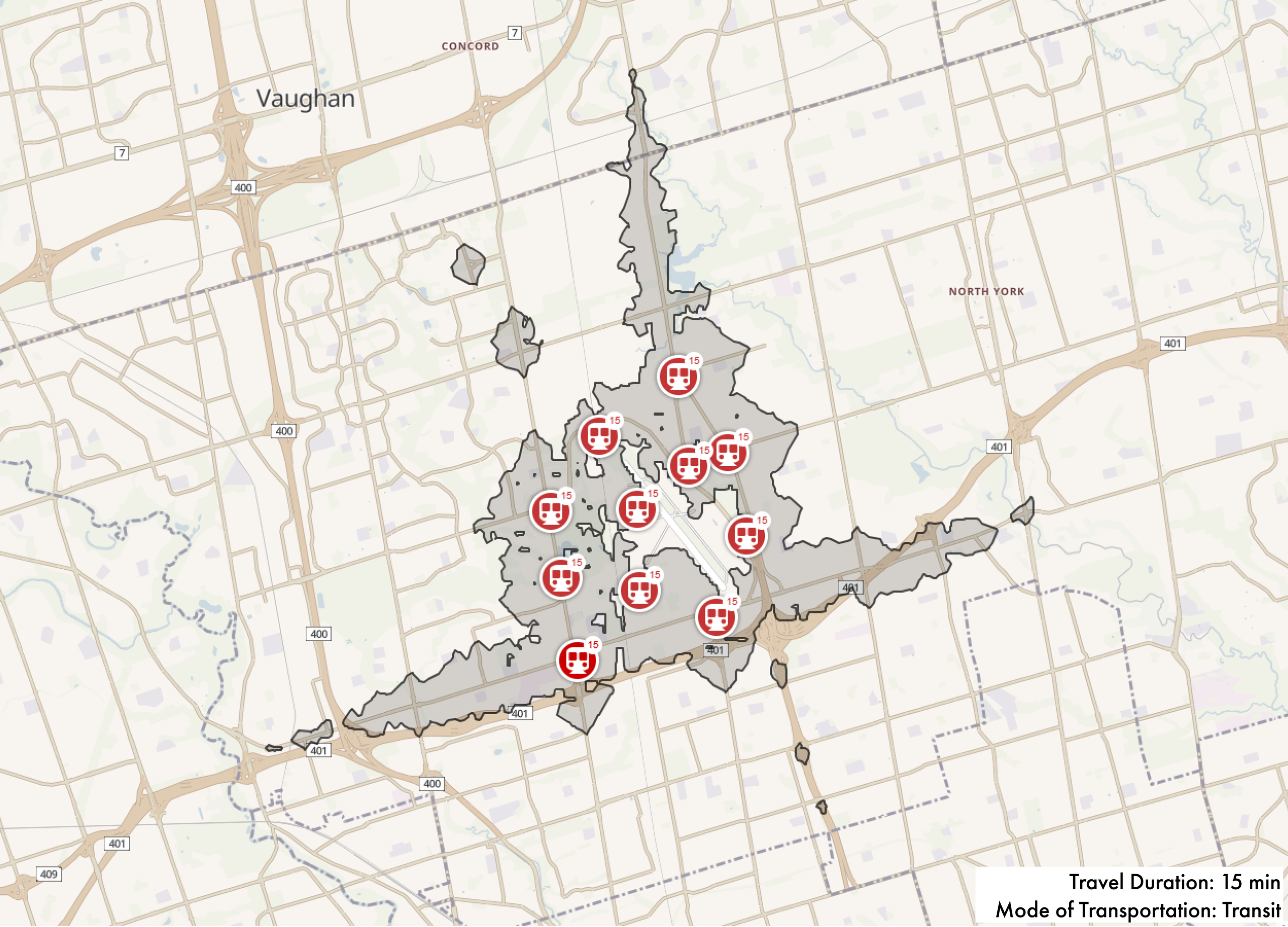

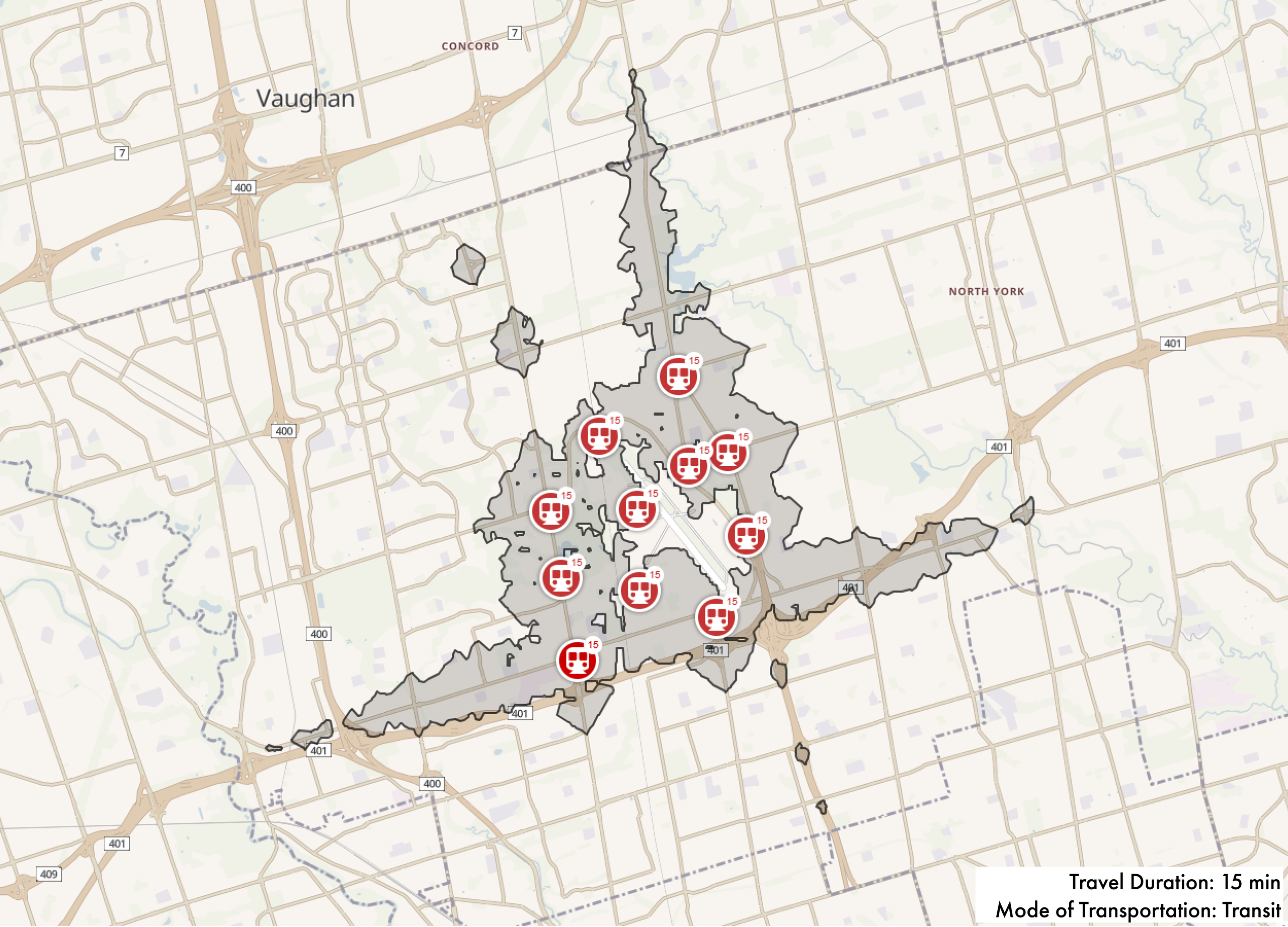

These diagrams show 15-minute travel reach using various forms of transportation, as well as lot types.

Hello

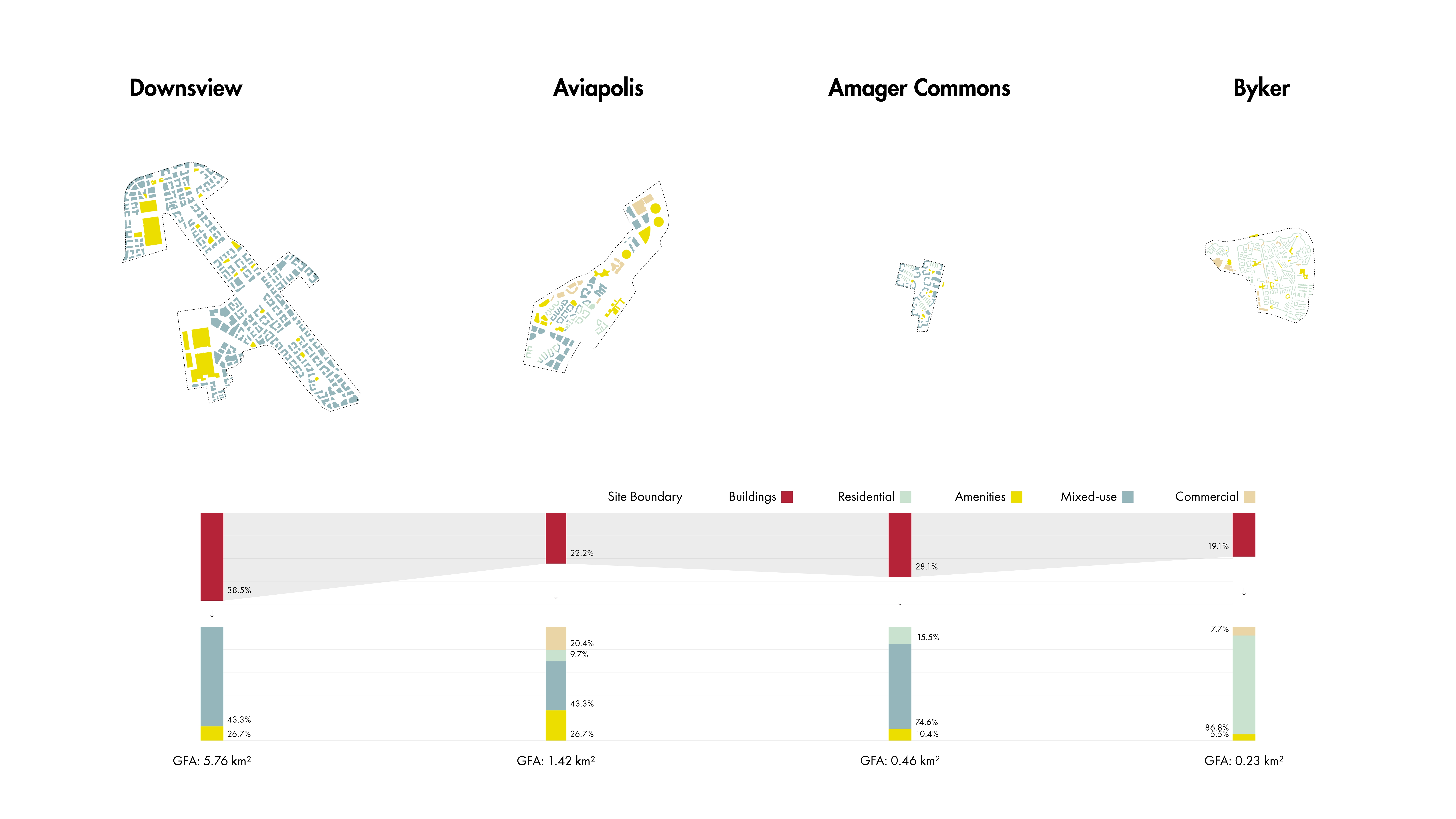

Vantaa, Finland

This masterplan materialized through a focus on connecting airport, nature, and city through walkable pathways. Located next to Helsinky Airport, this masterplan accomodates the growth of the region's commercial and service industries tied to the international airport.

Copenhagen, Denmark

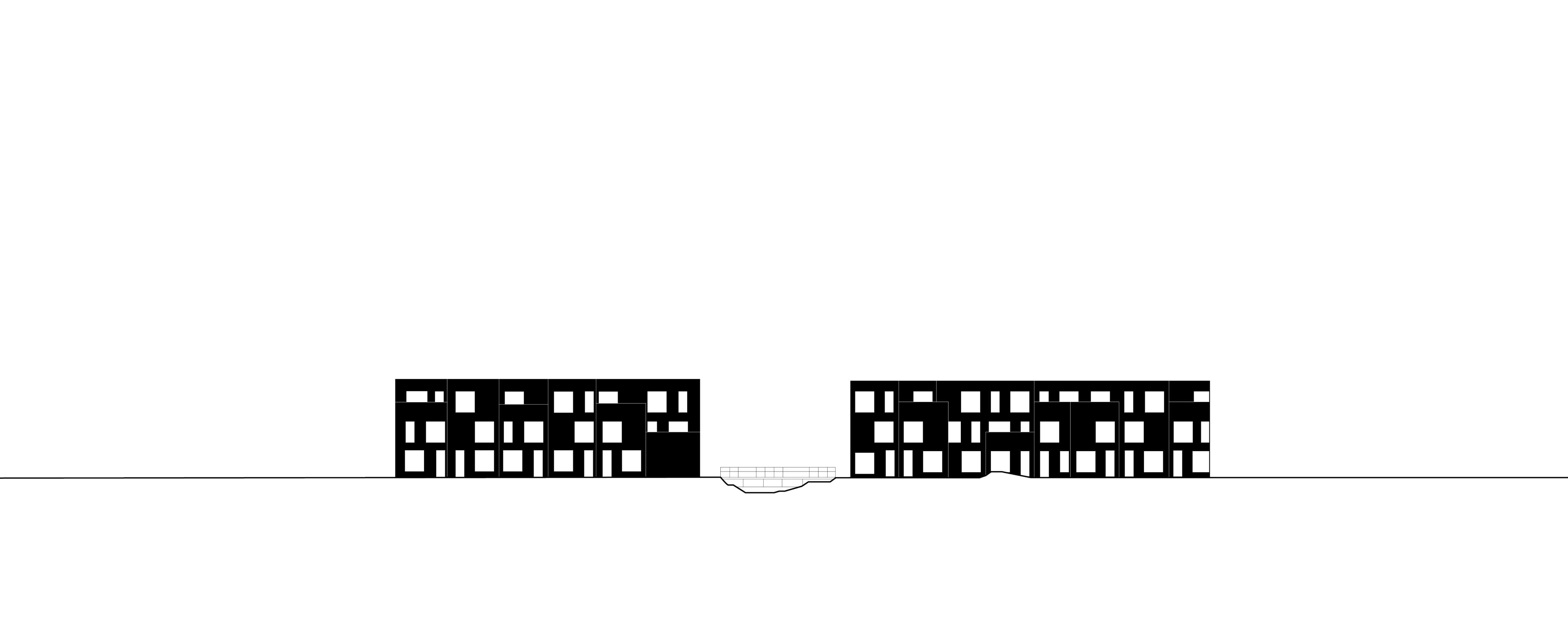

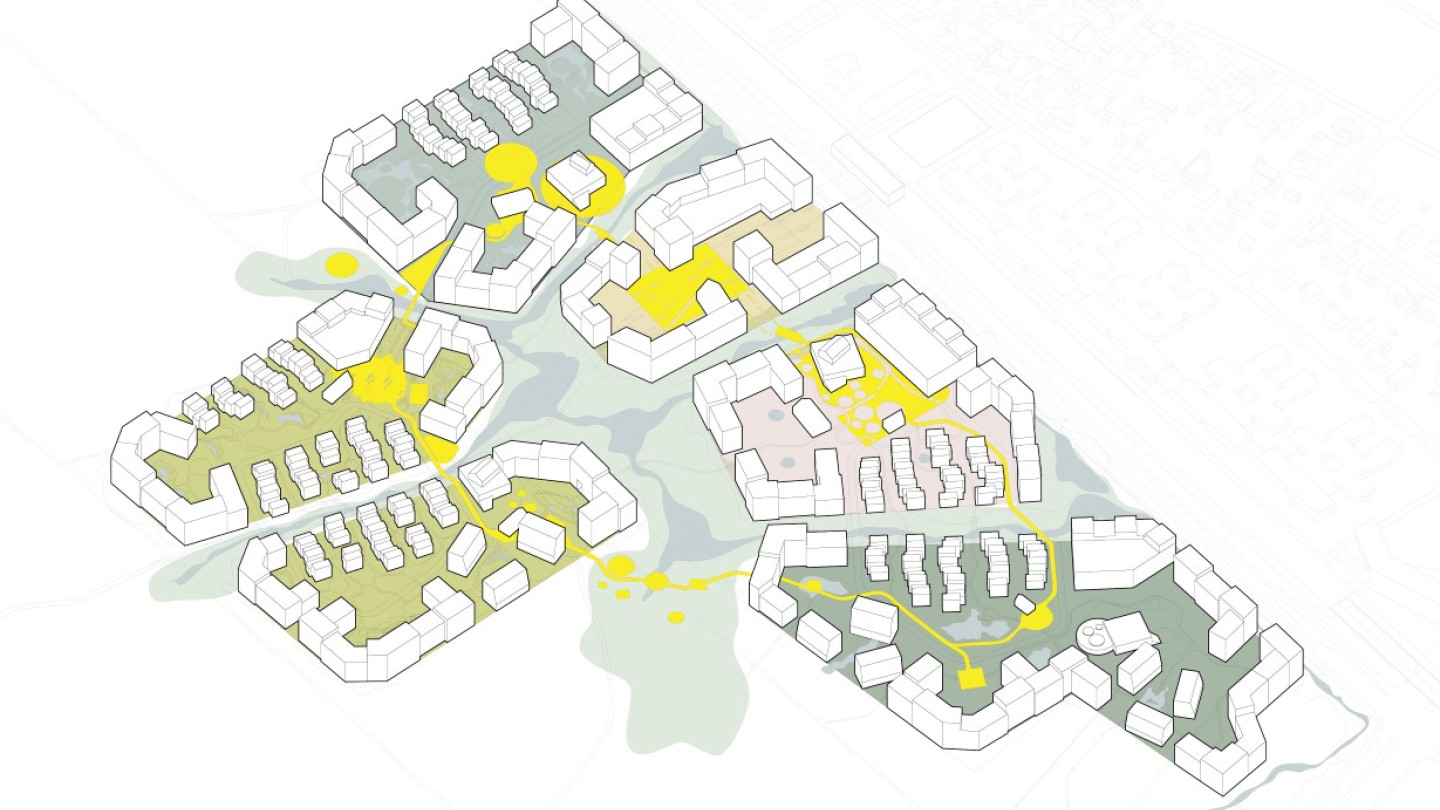

The Amager Commons master plan by CF Møller envisions a series of clustered, walkable communities that prioritize pedestrian traffic and limit car access, fostering close-knit neighborhoods with abundant green spaces, all designed within a low to mid-rise framework of urban islands and superblocks

New Castle Upon Tyne, UK

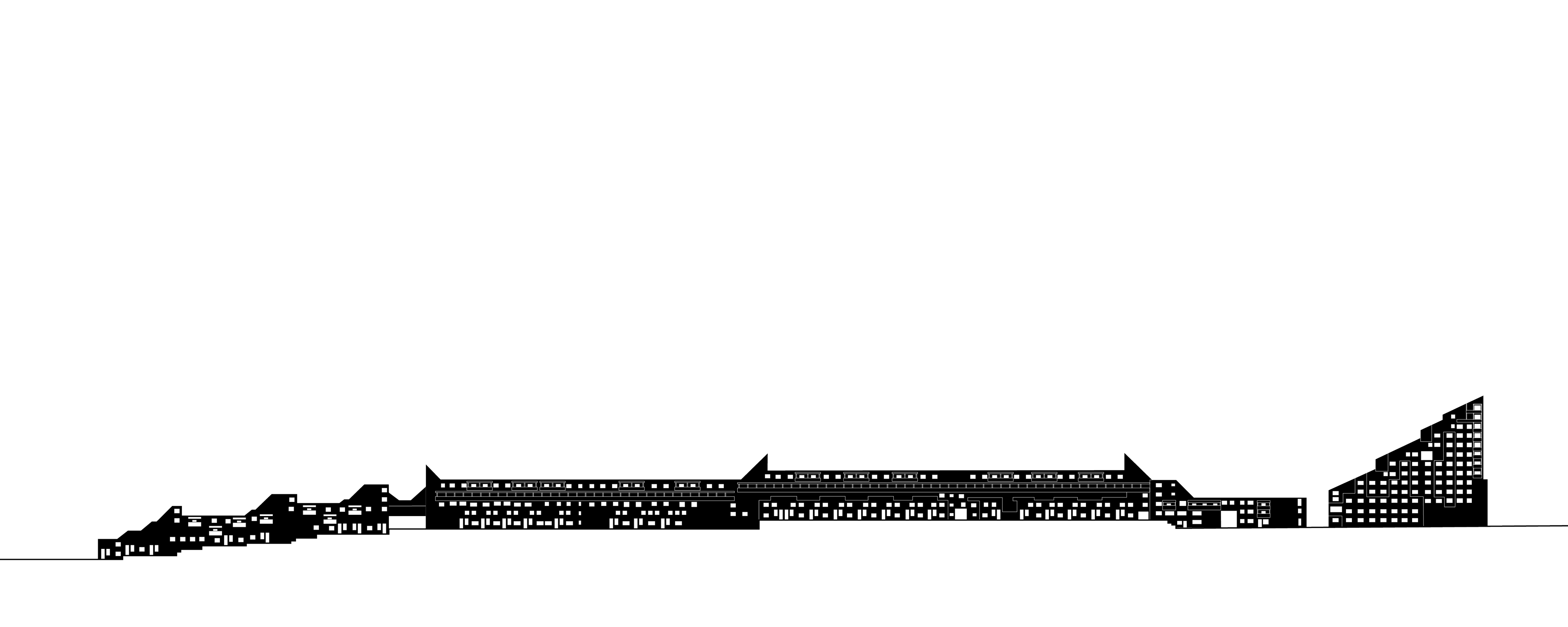

The Byker Wall embodies a set of key principles focused on community-centered design, social integration, and environmental responsiveness.

It prioritizes incorporating residents’ input, low-to-medium density housing, and pedestrian-friendly streets. The Wall acts as a barrier against noise and wind while fostering social interaction through communal spaces. Its use of vibrant colors and varied materials creates a human scale, making it a model for socially sustainable urban housing.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)